The Future of Objects and Materials

- Alex Gountras

- Dec 21, 2019

- 8 min read

Background

Since the beginning of civilization, humans have created, collected, bought, and sold objects made from a variety of materials. These objects have served countless purposes—

from furniture that provides comfort, to tools that harvest crops. They are often functional, sometimes symbolic, but always tied to our way of life. As we move into the future, these objects continue to evolve, becoming more technologically advanced with each iteration. The purpose of these advancements is typically to deliver greater comfort, efficiency, strength, or resilience. At times, entirely new objects emerge, building on the foundation of their predecessors and expanding what is possible for human life.

The creation of objects has changed dramatically over time. In early human history, bowls, weapons, and tools were crafted by hand to meet essential needs and improve survival. While many of these were personal creations, efficiency grew as humans developed ways to produce items in greater numbers. The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440 marked a leap forward. Later, the Industrial Revolution transformed production entirely, ushering in an era where mass-produced goods became both more affordable and more abundant—improving, and at times complicating, human life.

Yet all of these objects share one simple truth: they are made from the elements of the Earth. Everything we create can ultimately be traced back to the periodic table’s 118 elements. And while the elements themselves are finite, the combinations we can form from them are virtually limitless. Imagine, for a moment, if every object you owned could be broken down into its elemental makeup. What if we could measure the exact amounts and percentages of those elements, regardless of the object’s condition? It sounds unusual, even unsettling, because this is not how we typically think about the things we use and discard—but perhaps it should be.

As a species, we are skilled at transforming Earth’s elements into useful materials and products. But we are far less skilled at controlling where those objects end up when we are finished with them. Some break down naturally or are efficiently recycled, but many others linger with dangerous consequences. Discarded electronics, batteries, plastics, and other toxic materials seep into the environment, harming fragile ecosystems. Even recycling is not a perfect solution—materials are often shipped to unregulated countries where unsafe disposal practices, such as open burning, threaten both the planet and the people handling the waste.

If we could find more efficient, responsible ways to enjoy the benefits of these objects without inflicting harm on our health or environment, we would not only improve our quality of life, but also safeguard the future of the planet itself.

3D Printing and the Future

Let’s fast-forward to the 21st century. With the introduction of 3D printers, we’ve witnessed the dawn of a new era of creation. Today, with nothing more than a capable machine, a digital design, and some raw material, we can produce physical objects on demand. Most current 3D printing relies on plastics of varying strength and durability, enabling the creation of everyday products—and even functional objects with moving parts, like adjustable wrenches. For the first time, individuals can design and produce their own tools, prototypes, and original creations without the scale, cost, or red tape of factory manufacturing.

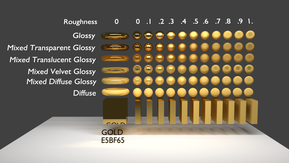

Yet, as exciting as this is, the first generation of 3D printing has clear limitations. Its genius lies in the concept, but it is constrained by the small number of usable materials. Over time, however, we can expect the palette of 3D printing to expand. Imagine producing silverware, car parts, or computer components directly from a printer. For this to become practical, the materials must be affordable, accessible, and scalable. As with many innovations, demand will drive progress, costs will fall, and this once-futuristic idea will become mainstream.

This evolution invites us to fundamentally rethink our relationship with objects and materials. After all, every object on Earth is composed of the same building blocks—the 118 elements of the periodic table. If we could harness those elements in a format similar to how a printer uses ink, the possibilities would be virtually endless. With the right combinations, we could create almost any object we desired. Even if it were possible to reliably harness only a subset of common, stable elements, the implications would still be profound.

As technology advances and costs decline, this type of elemental 3D printer could first find its place in commercial industries before eventually reaching households, much like the original 3D printers did.But creation is only half the equation. The real breakthrough will come when we can both assemble and disassemble objects at will:

Combine elements to create objects.

Break them down back into their original elements for reuse.

The second capability is harder to solve, but it’s no less important. Without it, we risk repeating the same cycle of waste and environmental harm. With it, we open the door to a circular ecosystem of creation—one where nothing is permanently discarded, and materials flow endlessly back into new forms.

This vision blends both sides of innovation: technology inspiring new possibilities, and human imagination pushing technology further. It’s a reminder that progress isn’t just about making more—it’s about making smarter, and with foresight.

A Brave New World

Perhaps the most important point to take away is how this type of innovation could truly reshape the world. If such an advanced printer were available to the general public, the possibilities would be virtually unlimited. Entire industries could be transformed—factories replaced by local, on-demand production; global shipping routes reduced as objects are printed where they are needed; households empowered to repair rather than replace. Commerce, monetization, and even supply chains would evolve. Most importantly, by recycling elements back into their raw form, we could reduce waste and dramatically lower our carbon footprint. This is not just innovation—it is a reimagining of how humanity creates, consumes, and sustains itself.

MANUFACTURING

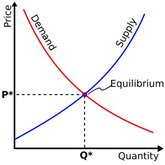

The ability to create and break down objects on demand is powerful. Humanity’s constant desire for new materials and tools is why so many forms of manufacturing exist today. Traditionally, this has required specialized machinery, labor, and infrastructure. The industrial revolution ushered in assembly lines that allowed us to produce at scale—driven by technology and demand. But just as factories once disrupted the workshop, another radical shift is inevitable when cost and demand for on-demand creation reach equilibrium.

With new technologies that can produce materials instantly, we’ll likely see production models move closer to communities and even individuals, rather than relying solely on centralized factories and global distribution. Larger facilities may still exist for oversized creations—vehicles, airplanes, massive machinery—but the everyday consumer could have production power at their fingertips.

In an era where people expect personalized, on-demand experiences, this technology would finally extend that expectation into the physical world. For companies, it could mean shifting from manufacturing goods to simply providing design instructions. Instead of shipping objects, they would distribute digital blueprints, letting the consumer—or their local hub—print exactly what is needed.

TRANSPORTATION

With this kind of innovation, the transportation industry would inevitably be transformed. Today, nearly every company depends on trucks, ships, planes, or trains to move goods. But if products could be created on demand, the need for mass distribution would shrink dramatically. For businesses, this would mean lower costs and faster delivery. For society, it could mean fewer emissions, less congestion on our roads, and a significant reduction in our environmental footprint.

Of course, this shift would also reshape jobs. Millions of people around the world earn a living in transportation and logistics today. While some of these roles may diminish, history shows that technological revolutions always create new opportunities. In this case, entirely new industries could emerge around maintaining, repairing, and supplying the printers themselves—just as renewable energy has created new careers even as fossil fuel jobs decline.

The real challenge is not whether change will happen, but how we prepare for it. Societies that anticipate these transitions—by re-skilling workers, supporting innovation, and designing thoughtful policies—will thrive. Those that resist will find themselves reacting in crisis instead of shaping the future.

COMMERCE

Over the last decade, commerce has dramatically shifted online. We can now compare, review, personalize, and order products with a few taps on a screen. This was the first major leap. But in a world with next-generation 3-D printers, we would take this interaction to the next iteration: true real-time, on-demand commerce.

In this landscape, companies would focus primarily on design, marketing, and service—not on manufacturing, warehousing, or distribution. Consumers could instantly purchase the design specifications for a product, and their printer would assemble it at home using the right combination of elements. The only “ingredients” required would be the elemental materials themselves.

This model would work much like digital downloads today. Instead of downloading a song or an ebook, you could “download” a new set of headphones, a coffee mug, or even furniture. Verification systems would ensure your specific printer could handle the object safely; if not, the system could recommend alternative production options.

The implications are enormous. Wait times for shipping would vanish. Costs would fall for companies. Environmental harm from factories, packaging, and transportation could be dramatically reduced. For consumers, the shopping experience would shift from delayed gratification to near-instant fulfillment.

Of course, safeguards would be essential. Just as app stores and streaming platforms regulate what can be downloaded, on-demand printing ecosystems would need rules to prevent illegal or unsafe objects from being created. Piracy of product blueprints could also spark new debates over intellectual property and ownership.

To summarize, this model wouldn’t necessarily replace all distribution methods overnight, but it could supplement—and eventually rival—the systems we rely on today. The result: a world where commerce is faster, cheaper, and far more sustainable than anything we’ve experienced before.

MONETIZATION

With a system that allows us to both create and deconstruct objects using the periodic elements, we open the door to an entirely new way of thinking about money. Instead of valuing objects for their brand, craftsmanship, or rarity in finished form, we might begin to value them for their elemental composition.

This could lead to a new type of economy—one where elements themselves are the currency. Elements with higher scarcity or utility would carry more weight in the marketplace, and people could trade them directly. Suddenly, all of the unused objects collecting dust in our homes—old electronics, broken furniture, outdated appliances—could be broken down into their elemental parts and converted into valuable, tradeable assets.

In today’s world, the closest equivalent is recycling. We recycle glass, metal, and paper, but even that system is limited. Not everything can be recycled, and the process often depends on conditions that reduce efficiency and value. In an elemental economy, however, the barrier to entry disappears. Every object, regardless of its condition, could be disassembled into base elements and reintegrated into the cycle of value.

This would not only reduce waste but also create a more circular, resource-efficient economy. Wealth would no longer be tied only to money in a bank account, but also to the latent elemental value of the objects we already own.

Reducing Our Carbon Footprint

In this new world, humanity could come closer than ever to achieving a near-zero carbon footprint. Every object would not only be recyclable, but inherently valuable. Instead of waste being a liability, it would become a form of wealth.

This creates a powerful ecosystem where recycling is no longer just a moral choice—it becomes the foundation of economic value. People would be motivated to recycle not simply because it’s “the right thing to do,” but because it directly benefits them. Broken electronics, worn-out furniture, or outdated devices would all be worth something, as their elements could be reclaimed and re-traded.

It is one thing to encourage people to act sustainably out of responsibility. It is something entirely different—and far more effective—to create an economy that rewards them for doing so. By aligning human self-interest with planetary well-being, this model could reduce waste on a massive scale while also strengthening individual wealth and community prosperity.

Comments